From Apulia.

The painting depicts the birth of Helen of Troy. According to the myth, Helen comes to being through the union of Zeus and Leda. Zeus approaches Leda in the form of a swan. Because he is in the form of a swan, Leda lays eggs, and upon hatching, Helen is born. This image is based on a comedy (The man with an ax has a comedic eyebrow, and each of the men is wearing a penis, a prop always used in the play, imitating Priapus). Because of the loss of the play, we are not informed about the content of this painting. We only know through mere visual facts that a man is raising an ax. Maybe he is helping Helen out, or he is afraid of Helen to be a monster because she is born from an egg. Another man is on the right, lifting his hand to the sky. Maybe he is praying to God. Also, a woman is peeping into the room.

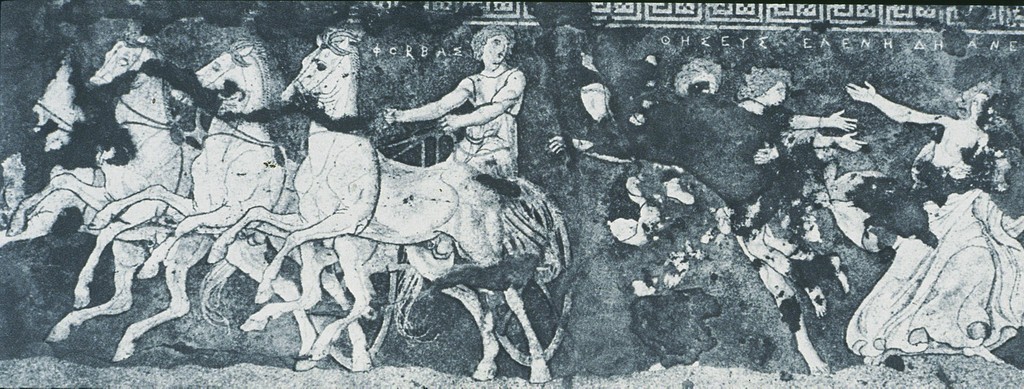

The picture illustrates the abduction of Helen by Theseus. To the left, the charioteer Phorbas is holding the chariot ready. On the right side of the picture, a relative or friend of Helen named Deianeira extends her arm to offer help Helen. The center of the image is not clear about what is happening, perhaps capturing the chaotic moment perfectly. One thing interesting is that there are four horses holding the chariot, which generally used until the Iron Age, rather than the Bronze Age when this abduction happens. This drawing strategy indicates that though the content initially occurs in the Bronze Age, the cultural element would change corresponding to the need of different times. No wonder Homer’s Iliad contains plenty of later era’s attributes. Other sources and documentations, like this pebble mosaic, are also intervened by cultural distortion. Also, the facial expression of the chariot rider Phorbas shows the expertise of the painter.

David depicts the lovers embracing in a secluded and sumptuous bedroom, which differs from his previous work in its choice of amatory rather than heroic or didactic subject. David perceives this commission as an opportunity to explore new aesthetic terrain by focusing on the complexities of mythology as an intellectual category.

Like that female character, Paris impossibly contorts his body so that his head faces Helen with his left cheek in full profile. His eyes gaze directly towards her to make complete eye contact. Finally, his muscular right arm grasps her left arm and appears to be both bringing her closer and pulling her down. It is Paris’ body that bespeaks a desire and eagerness. Helen’s pose, on the other hand, is languid and evokes no mutual desire. She stands half a head taller than the seated Paris even though her body is hunched over. Except for her legs and feet, which cross and subtly imply backward motion, the body is limp. Her arm is so carelessly draped over Paris’ right shoulder that it appears she is unaware of the limb. Her eyes do not reciprocate Paris’ glance and look blankly downward toward the ground. She lacks control of her movement and yields herself half-heartedly to the embrace of her lover. This scene represents the moment after which Paris has made his case to the resigned Helen in the Homeric text:

No more dear one—don’t rake me with your taunts,

Myself and all my courage. This time, true,

Menelaus has won the day thanks to Athena.

I’ll bring him down tomorrow.

Even we have gods who battle on our side.

But come—

Let’s go to bed, let’s lose ourselves in love!

Never has longing for you overwhelmed me so,

No, not even then, I tell you, that first time

When I swept you up from the lovely hills of Lacedaemon,

Sailed you off and away in the racing deep-sea ships

And we went and locked in love on Rocky Island…

That was nothing to how I hunger for you now—

Irresistible longing lays me low!

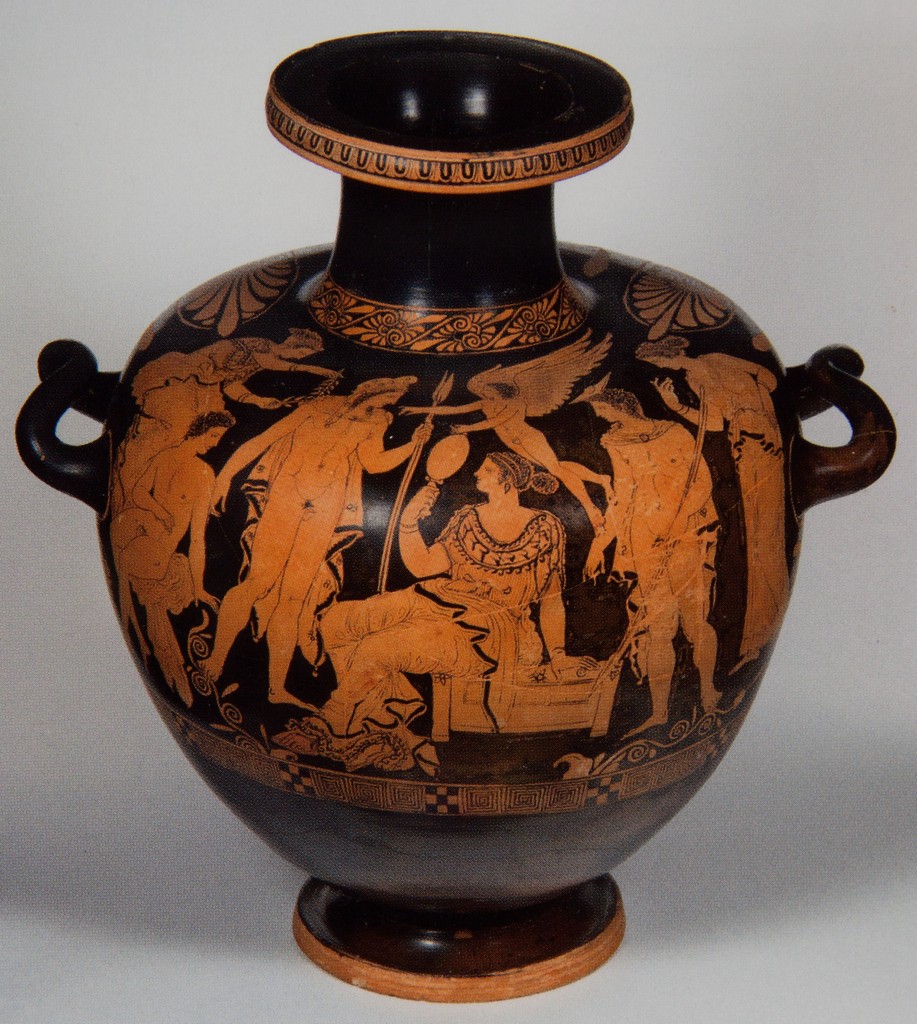

From Kymisala, ancient city located about 70 km south of Rhodes. Vase painting attributed to the Jena Painter.

The vase painting decorates a water-jar or hydria, a vessel which has an important place in women’s lives. This one is probably an object from a grave. Paris, the son of King Priam, is standing and looking at Helen while Helen is sitting and seemingly holding a mirror upon, which emphasizes her beauty. Helen and Paris are in the center of the painting, and behind them, individuals are listening to the conversation taking part. This painting has no specific background storyline to support the content but is only a random meeting between Paris and Helen. The scene also depicts an angel on top, perhaps guarding the daughter of Zeus, or he is Cupid, which indicates the love affair between Paris and Helen. On Helen’s right side is Himeros, the God of uncontrolled desire. There are other Gods of passions present in this painting, for example, Peitho and Habrosyne. Because of the displays of these Gods, we can infer this event roughly happens when Paris and Helen meet each other in Sparta, and soonly Helen is taken to Troy by Paris.

There are two possible interpretations of this Stela. The first one is that Menelaus is wooing Helen. On the left, Menelaus, with fillet binding his short, neatly-trimmed hair, stepped toward youthful Helen. His left arm raised and resting on her shoulder, his hand reached around her neck and held her hair on the side facing the viewer, and his right hand extended to clasp her left hand; Helen, hair loose indicating she is still a maiden, proffering wreath held in the left hand to Menelaus.

The second one is: Menelaus was threatening Helen. Menelaus with long hair and beard strode toward Helen. His body bent forward slightly in agitation, left arm raised and on Helen’s shoulder as though trying to get a grip on her, and right hand pulled back, holding the sword with which he is threatening to slay his wife; Helen, veiled as sign of mature, married woman, standing almost impassively, left hand raised and touching the sword as if to stop death blow. The marriage of Menelaus and Helen and their reunion after the Trojan War were not part of the Homeric cycle but belong instead to the poems written approximately one hundred years later, in the eighth century B.C. These non-Homeric poems were to prove far more popular than the Iliad and the Odyssey as sources of subjects for both the representational arts and the tragedies. The first subject of our Stela went even farther in depicting a scene for which there was no literary evidence. From the Catalogue of Women, attributed to Hesiod but written, probably, in the mid-eighth century, we learn that when Tyndareus made his step-daughter Helen available for marriage, many suitors, all great heroes, came bearing gifts. Among them was Agamemnon, who “being son-in-law to Tyndareus, wooed her for his brother Menelaus.” This tradition persisted in all Greek literature.

But a recently found inscription makes it clear that numerous shield-bands depicted a scene like this, which is identified as Menelaus wooing Helen. The self-confident ruler stepped forward to grasp his future wife. Schefold pointed out that the archaic Greeks were anxious to determine the reasons behind things and therefore seized upon the detailing of Helen’s life as part of their fascination with the cause of the Trojan War.

The marriage of Helen and Menelaus was doomed to failure because Tyndareus, years previous, had failed to sacrifice to Aphrodite. In revenge, the goddess made all three daughters – Clytemnestra, Tymandra, and Helen – notorious for their adulteries. Thus Electra, in Euripides’ Orestes, cried out, “Tyndareus begat a race of daughters notorious for the shame they earned, infamous throughout Hellas.”The cause of Electra’s cry was the news that Menelaus had returned from Troy, bringing Helen with him. The reunion of husband and wife, which resulted in their eventual return to Greece, was challenging to be particular about.

The sixth-century Sicilian Stesichorus was credited with creating the first version of the story in which Helen went to Egypt, and only her wraith remained in Troy. This story formed the plotline of Euripides’ Helena, in which the grieving Menelaus finally arrived in Egypt to find Helen about to wed an Egyptian ruler. The antiquity of this version was dubious. More likely, the original epic poem dealt with this subject (cf. for example, Lesches’ Little Iliad of ca. 750 B.C.) told of Menelaus coming to take Helen from Deiphobus. The artist had chosen to represent the moment just after the death of Deiphobus when Menelaus stepped forward to slay Helen. It was at this point, according to Lampito in Aristophanes’ Lysistrata, “Menelaus, when he saw Helen’s naked bosom, threw away his sword, they say.”

Interesting throughout the various versions of the mythology centering around Helen was the ambiguity of attitude which men expressed toward her. Agamemnon, in Euripides’ Iphigenia in Aulis, said to Menelaus, “Why you are mad yourself, seeking a wicked wife once rid of her,” a sentiment with which Menelaus himself agreed later in the play. Yet in the Helena Menelaus expressed no bitterness at all toward Helen, saved the years he wasted at Troy when she was actually in Egypt. When Orestes (in the Orestes ) saod of Agamemnon that “If he is bringing his wife with him he is bringing a load of evil,” he expressed what most Greeks felt about this daughter of Leda and Zeus. Yet she continued to enthrall men. Even during the midst of the battle at Troy, Achilles was said to have been overcome by her beauty and to have fallen in love with her. Graves himself tried to explain her out of the Trojan War altogether by viewing the suitors of Helen as those who were mindful of the Hellespont, a linguistic argument that was highly debatable.

We know that Helen was once a nature goddess of farther-reaching provenance than Graves’ suggested Spartan moon-goddess (cf. 3Gc.020). What we do not know is the transformation she underwent between Mycenaean times and just barely post-Homeric days. She losed her status as a goddess, but it was clear that she retained her aura of primitive feminine power. In post-classical times Helen was reduced to a cheap human temptress and, like Medea (cf. 3Ha.125), was then only a nasty woman. From the eighth century to the late fifth century, she continued to be an influential feminine figure. Exactly how we are to read her role during this period is difficult to determine, but that she haunts the emerging consciousness of Greek culture is unquestionable.

99 1/2×104 1/4″

Helen was the wife of King Menelaus of Sparta. Paris, a Trojan prince, seduced Helen. This affair began the Trojan War. Accounts of their love story tend to differ. Some writers recorded that Helen fell in love with Paris. Others believed that she was unwillingly ‘abducted’ or ‘stolen’ from her husband. In this painting, Helen, followed by her ladies in waiting, is depicted at the center of the composition. She is led away by Paris, who sports a plumed helmet, and is accompanied by his soldiers. To the far right, two figures regard ships at sea. Incidental foreground details include a black boy, a small lapdog, and Cupid with his bow who turns to see the viewer with complicity. Paris looks directly into Helen’s face, while Helen pays no attention to Paris, and even seems distressed down to the ground. This contrast suggests that Helen is not willing to leave with Paris. However, there are Cupid on the right corner of the picture, which indicates it will happen to be love. Still, we are not convinced whether the Cupid represents the presence of love, or his image is preferably an irony for the abduction.