Scherer, Margaret R. 1967. “Helen Of Troy”. The Metropolitan Museum Of Art Bulletin, New Series 25 (10): 367-383. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3258426.

Homer’s Iliad told little of Helen’s story. This article focuses on talking about other Medieval plays that described some famous stories of Helen with a view different from Homer. As Christianity gradually superseded paganism and the classical civilizations of Greece and Rome entered their long transition to the Middle Ages, the shape of the Trojan story changed, according to social and cultural needs. For instance, Dares, in his book, The History of the Destruction of Troy, showed that the sympathies of Europe were shifting to the Trojan side, and gradually the Trojans rather than the Greeks became the heroes of the tale, with the image of the Greeks transformed into medieval knights. In this way, they consider Helen to be innocent. For instance, the Cypria gave an underlying cause, which emphasized the Greek concept of fate, that it was Zeus planning with Themis [goddess of order] to bring about the Trojan War.

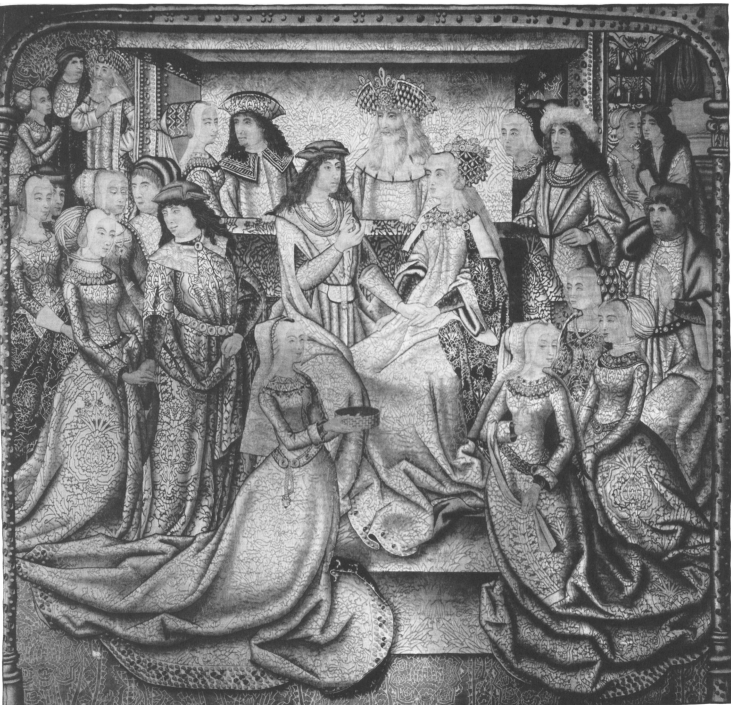

Moreover, Medieval romances changed the story of Helen’s abduction radically. In the Middle Ages, people were so emphatic about the Trojan heroes that it was unthinkable for a Trojan to steal his host’s wife from a home where he had entertainments. Thus, when Paris and Helen caught sight of each other, their mutual passion flamed. The medieval romance also found in the welcome of a beautiful queen and the opportunity of showing the pageantry of royal entries. Many paintings left showed this tendency, for instance, The Marriage of Paris and Helen. Homer depicted in Odysseus that Helen lived with Menelaus in harmony and comfort. Euripides also wrote in drama Helen that Menelaus found the real Helen in Egypt. Then the phantom of Helen in Troy vanished. The medieval romances, on the other hand, told that the Greeks felt considerable enmity against Helen after the fall of Troy. Pausanius, a second century A.D. author, told several versions of Helen’s end: Her grave was on the island of Therapne with Menelaus; the jealous queen hanged Helen on the island of Rhodes after Menelaus’ death, and Helen lived in the White Isle with Achilles.

In short, the story of Helen and the attitude people treated towards Helen were not precisely accessible for us nowadays. They varied according to different cultural propagandas. That is the reason that so many versions of her stories are left and sang by us.

Blondell, Ruby. 2018. “Helen And The Divine Defense: Homer, Gorgias, Euripides”. Classical Philology 113 (2): 113-133. doi:10.1086/696821.

In this article, the author wants to look at the difference among these contexts, individually and together, for his interpretation of the argument that he calls the divine defense: he claims that one is not responsible for one’s actions if a god caused them. He shall focus on the three principle occasions when this argument is used to exonerate Helen of Troy.

The tension is: the god was, of course, heavily involved in Helen’s elopement. Zeus begot her specifically to make men fight over her beauty, and, at the Judgment of Paris, Aphrodite offered “marriage to Helen” as a bribe. However, these sources agreed that she left her husband willingly, driven by her desire. In such cases, divine influence on human behavior did not typically remove human responsibility. The three contexts were significantly different, in which the divine defense of Helen, as used in these three texts and uttered in different ways – both internal and external – was fundamental to its precise import in each case.

For Homer, it is in Priam’s voice that we hear the divine defense used on Helen’s behalf. He was addressing Helen herself, in a private conversation, as they looked down from the walls of Troy at the duel between Paris and Menelaus. He said that “In my view, you are not responsible, but the gods are responsible, who stirred up lamentable war with the Achaians.” In this case, the tension between the self-blame of Helen allowed Priam to applicate the divine defense as a face-saver on behalf of another person rather than oneself.

For Gorgias, the defense speech was argued by the sophist that Helen should not be held responsible for eloping if she “did what she did” under the influence of the gods. Gorgias developed his argument in a way that challenged the foundations of the moral order by threatening to eliminate human responsibility as such and with it all moral judgment, praise, and blame. In other words, he defied traditional views about human responsibility grounded in the principle of double determination. Though the perspective and critical point were similar to Homer’s settings, this internal context of utterance for Gorgias’ use of the divine defense was a public gathering where a man was speaking on behalf of an absent woman, a passive and powerless object or vehicle, to an assembly of other men. However, though Gorgias claimed that his goal was to arouse pity for Helen, this detached stance of Helen distances us from sympathizing with her.

For Euripides, he gave Helen an unparalleled opportunity to defend herself at length for her elopement. This argument was structurally similar to those we saw in Homer and Gorgias. Helen’s self-denial of double determination constituted a shameless refusal of personal responsibility. Talking about herself made herself hateful for Trojan women, and departed appropriately feminine comportment. Thus, Helen’s death sentence stood.

Skutsch, Otto. 1987. “Helen, Her Name And Nature”. The Journal Of Hellenic Studies 107: 188-193. doi:10.2307/630087.

The author claims that to put forward ideas on the name and nature of Helen may seem hazardous because of the uncertainty of the evidence. Nevertheless, the author shall attempt to outline the problems. If the author proposes any solution, the solution should be tentative.

In the treatment of myth, two tendencies were strong: it became fashionable to equate Greek mythological names with those of India. The other one was to reduce all mythological figures to natural phenomena.

Helen was mostly known as a tree goddess or, more generally, a goddess of vegetation. Another theory said that Helen went away to the south like the sun when the winter came. In addition, Helen, with her brother, were divine twins known to many of the Indo-European tribes. In Germanic mythology, their stories were all related to the sun.

There might be two mythological Helens. Not only because of the different functions shown above, but also because there were different sources, it showed that there existed “Helen,” the name without digamma (Corinth), and with digamma (which means the swift one). Though it may be tempting to ascribe the spelling to the influence of Homer, little influence of Homer appeared in the form of the other name on Corinth. We shall see below a difference in the functions of the different spelling of “Helen,” which strongly suggests that we have to do more investigation with two different names.

Regarding the one with initial “s,” if made into a name, it would mean “the shining one.” That name fit the vegetation goddess who receded to the south like the sun extremely well. Firstly, the Spartan goddess and Helen of Troy were identical, that the vegetation goddess was liked with Menelaus in their cult at Therapne. Secondly, as the shining one, her name connected with lights other than the sun, especially torch and the corposant, as depicted in many other plays than Homer’s.

In short, the author tries to combine Helen without a digamma with Helen with a digamma. However, others think there are no exact parallels for the relation, but there are dedications with the demonstrative pronoun. The author still holds that it is likely that, among a group of items dedicated, so small an object as a ring would bear the dedicatory inscription.

Hughes, Bettany. 2005. Helen Of Troy. London: Jonathan Cape.

Blondell, Ruby. 2013. Helen Of Troy: Beauty, Myth, Devastation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Austin, Norman. 1994. Helen Of Troy And Her Shameless Phantom. New York: Cornell University Press.